By John Brush

Doves and pigeons are used are some of the most familiar species of birds in the world; they are commonly hunted, bred as a hobby, kept as pets, and frequently seen in towns and cities. There are 8 species found in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, making our area one of the most dove diverse regions in the United States. Let’s go through the line-up!

Rock Pigeons have had a variety of names and nicknames over the years: Rock Dove, Feral Pigeon, Domestic Pigeon, Homing Pigeon, War Pigeon, and Flying Rat. (photo by Jason Jakymowycz)

We have two species of pigeon in the Valley: Rock Pigeon and Red-billed Pigeon. Note that “dove” and “pigeon” are sometimes used interchangeably, but typically birds called pigeons are larger than those called doves. Due to the many feral populations established in towns and cities, Rock Pigeons (a Eurasian species) are one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, and are spread across almost all of the Americas (where they were introduced in the 1600’s).

The beautiful Red-billed Pigeon can only be found in the United States between Laredo and Rio Grande City. (photo by Tripp Davenport)

The Red-billed Pigeon is not a cosmopolitan species, as they are only found in Mexico and Central America. Though common in much of Central America, these purple-maroon plumaged pigeons are only found in the United States between Laredo and Rio Grande City, TX. This species is one of the most sought-after by visiting birders, and often leads to excited whoops and hollers when seen.

There are four medium to large sized doves that inhabit the Valley: Mourning Dove, Eurasian Collared-Dove, White-winged Dove, and White-tipped Dove. Mourning Doves are common across the United States, and are readily identified by their long tail and black spots on their wings.

Eurasian Collared-Doves were accidentally released in the Bahamas about 40 years ago, and they have spread across the United States at a rapid rate. (photo by Derek Iden)

Mourning Doves can often be seen perched on wires along fences or between telephone poles with their long tails sticking out behind and below them. (photo by John Brush)

The Eurasian Collared-Dove is another non-native species that has successfully invaded North America. They established a population in Florida in the 1980’s, and have quickly spread over most of North America. Their three note “coo-COO-coo” is now a regular sound in urban areas across the Valley.

White-winged Doves were historically a species that occupied the southwestern United States with their densest populations here in South Texas. However, they too have spread and are now seen further northward. They are perhaps the most abundant dove in the Valley, and their “who-cooks-for-you?” calls are often the first thing you hear on a hot summer morning and the last thing you hear before the sun sets.

White-tipped Doves are one of the largest dove species found inthe LRGV. They are usually found under feeders (seen here with an Inca Dove) or running away to the safety of the woods. (photo by Erik Bruhnke)

Similarly named, the large White-tipped Dove is a much more shy bird than the White-winged Dove. They prefer to be in thick forests, and unless they venture out to a bird feeder, are typically seen running to the safety of the woods. Found from South Texas down into South America, White-tipped Doves give a call that sounds like someone blowing across the top of a bottle.

Last, and least in size, are the two smallest doves in the Valley; the Common Ground-Dove and the Inca Dove, measuring in at around 6.5 and 8.5 inches respectively. The Inca Dove is a longer bird because of its long tail, a feature that helps distinguish it from the shorter-tailed Common Ground-Dove. Inca Doves are also much more likely to be found in urban areas than are Common Ground-Doves, which tend to be in more rural and open brush land habitats.

The Common Ground-Dove is the smallest dove in the LRGV and is just a little bigger than a House Sparrow. (photo by Erik Bruhnke)

While many doves and pigeons in the Valley are quite common, aside from the Red-billed Pigeon, that should not mean they are underappreciated. The subtle differences in color, the various shades of blue skin around the eyes, and the generally calming coos of all our doves make them one of my favorite bird groups. I hope you will take time to look closer at the next dove that visits your yard, and enjoy the subtleties they offer.

The small Inca Dove looks like it is covered in fish scales and has an easily identifiable call: “WHIRL pool, WHIRL pool”.

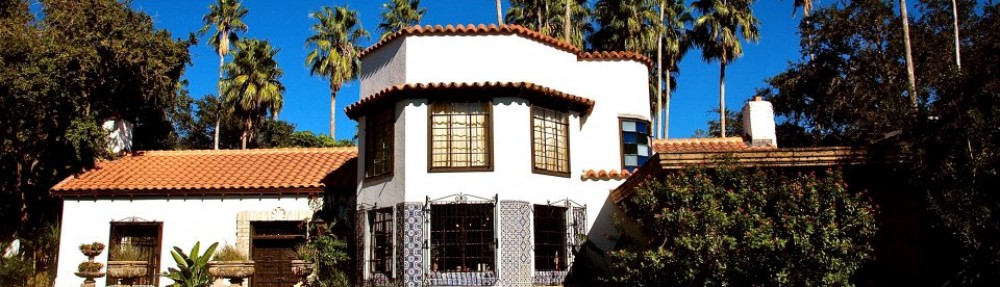

Join us at Quinta Mazatlan World Birding Center every Tuesday and Saturday morning 8am-9:30am for a Songbird Stroll. Last week we found seven species of dove during the walk as well as spring migrants. Quinta Mazatlan is located one block south of La Plaza Mall on 600 Sunset Drive, McAllen, TX. For more information visit http://www.quintamazatlan.com or call (956) 681-3700.

All birds in the family Columbidae (doves and pigeons) have the ability to drink by sucking or pumping water into their throats. This is certainly convenient on a hot day when all you want to do is stick your whole face in a cool pond. (White-winged Dove photo by Michelle Summers)